When spoon collectors confess their collecting passion to the uninitiated, they are invariably met with, at best, a raised eyebrow! How, they ask, could the humble spoon, an object that has been in use for thousands of years and with which most people feel quite familiar, offer such a rich and exciting collector’s field?!

Unlike many items of early secular or religious silver holloware, silver spoons dating from as early as the 14th century survive in relative abundance. Their changing styles weave a thread through the centuries, tracing and reflecting fashions, socio-political events, geography and industrial progress. It is this variety in style and design that makes them such an exciting and varied subject for collectors. Perhaps as a result of their size and portability – a spoon was an individual’s personal property and therefore travelled with them - spoons moved about, were stolen, hidden, exchanged and lost, and therefore crop up unexpectedly and in surprising places. In 1971, for example, a silver spoon dating from the early years of Henry VIII’s reign was found in the roof of a house in Devon! It is now housed in the British Museum.

In the Medieval and Tudor periods, a spoon functioned as both a practical necessity and a status symbol. While today an individual might seek to impress by turning up to dinner in a Maserati, a Tudor gentleman would have sought to create a similar impression by bringing with him a lavish spoon with which to eat! Silver spoons are also associated with a long tradition of gifting, and were often bestowed as christening or wedding presents. As a result, early spoons are frequently found with prick dot or scratch engraved initials and dates to their bowls or button terminals.

Sold in the Fine & Decorative, November 2022 Sale

Unlike some collector’s fields, where it can be hard to collect on a budget, there is a category of spoons for every purse. While the oldest and most exceptional examples can set you back tens of thousands of pounds, interesting 18th and 19th century spoons can be picked up at auction for a fraction of this price. Unlike large artworks, they are easy to store and display, and the varying levels of craftsmanship and condition mean that buyers can begin by collecting less expensive examples and trade these in as they go, thereby gradually improving a collection. Collectors will often bid fiercely for a particular spoon that they wish to add to their collection, not least because the average wait for a spoon to return to the market having been purchased is approximately 20-30 years.

Having decided which area of the spoon collecting field to focus upon (for example a geographical location such as Barnstaple or Norwich; a type such as slip top spoons or dog-nose spoons; a style of decoration, such as 19th century ‘private die’ spoons, or a date range such as 1550-1650), there are a number of factors to consider when deciding whether to purchase a particular spoon for a collection. As a starting point, we have chosen to focus on four of these factors below.

Hallmarks

Spoons with a good, clear set of hallmarks tend to sell for a premium. Hundreds of years of wear and tear, cleaning and general use take their toll on the marks stamped on spoons, with some becoming so ‘rubbed’ that they are barely legible. Generally speaking, the more readable the mark, the more desirable and saleable the spoon. You may come across hallmarks described as ‘pinched’; particularly on dog-nose spoons. These occur when the assayer punches the silver too forcefully, widening the stem so that the silversmith has to reshape it with his hammer. The effect is to squash the marks into a compressed shape, which often makes them more difficult to read and can detract from a spoon’s value.

Lot 73: A good set of hallmarks on a pair of Commonwealth silver Puritan spoons

by Steven Venables, London, 1659

Sold in the Fine & Decorative, November 2022 Sale

Condition

Every spoon collector will have their own criteria when it comes to assessing the condition of a spoon. That said, there are certain condition issues that are generally taken into consideration by most before making a purchase. Many collectors will choose to avoid spoons with splits and repairs, or those that have been modified or overpolished. Worn hallmarks and misshapen bowls may also render a spoon less valuable, as well as later gilding and later decoration or initialling. As a general rule, a spoon that looks tired or worn out will sell for less than a comparable example in a better state. When assessing a spoon in the hand, it might be possible to detect areas of thinness where initials or crests have been erased. This thinning is not considered desirable and detracts from the value of the spoon.

Craftsmanship and Proportions

While ‘all men were created equal’, the same cannot be said for spoons! Many early spoons were custom made for an individual and the common practice was for a client to be charged for the weight of the silver used, with a separate charge applied for the fashioning of the piece. As a result, spoons vary considerably in their gauge and quality. The best master craftsmen fashioned spoons with excellent proportions and symmetry, and a spoon with poor proportions should be examined carefully. A misshapen bowl may denote a repair, while a disproportionately large apostle finial, for example, may indicate that the finial has been replaced, or that the spoon is a later example masquerading as an early piece.

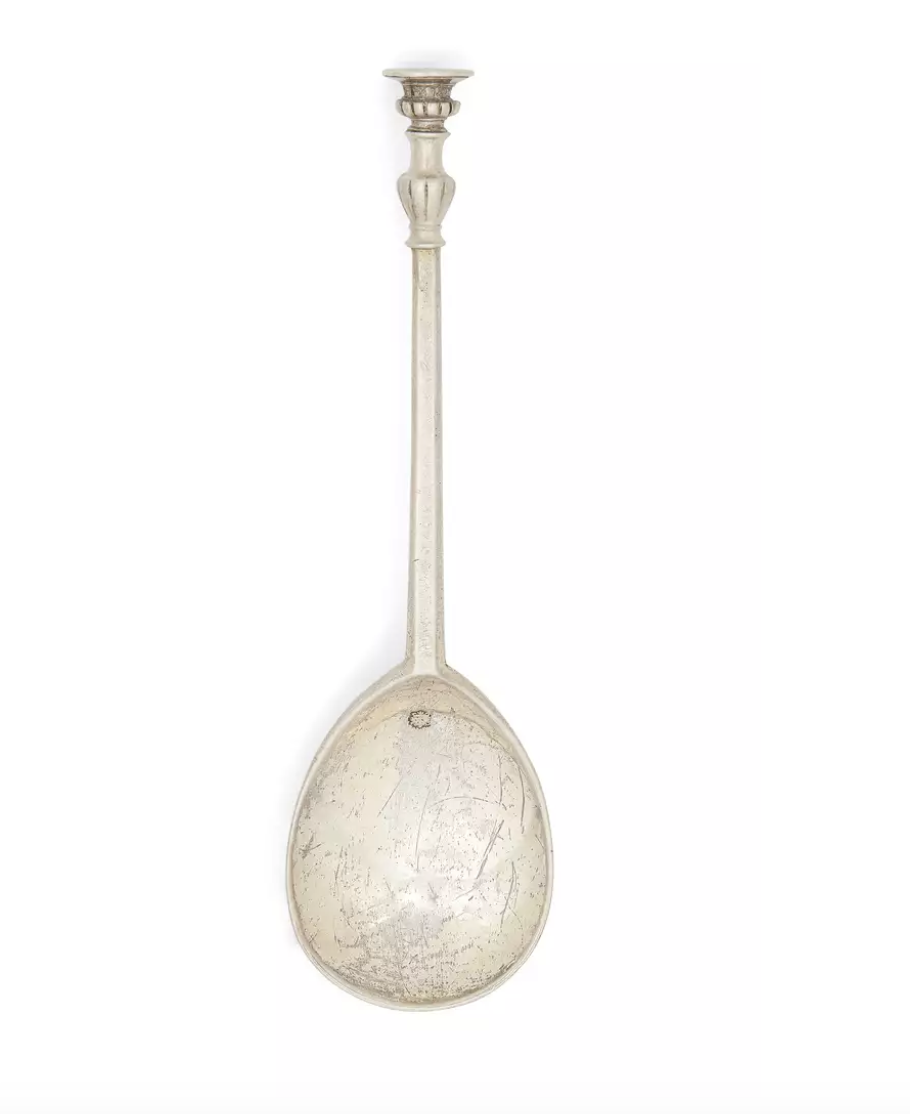

Lot 11: A good example of an Elizabeth I baluster seal top spoon showing

a well-proportioned bowl and terminal

Provenance

Spoons that have formed part of a private collection or have provenance to confirm family connections or an interesting origin may sell for a premium. Examples of significant collections of early spoons include: The Benson Collection; The Albert Collection; The Jackson Collection and the Constable Collection. Many early spoons have been handed down in wills and recorded in inventories, and are therefore traceable; a factor which tends to add to their value. Due in part to the lack of available surface area for engraving, crests and coats of arms are rarely found on spoons prior to the 18th century, so tracing the provenance by way of heraldry is rarely possible.

Examples of early and interesting spoons sold at Roseberys:

- LOT 154: An 18th century provincial silver Hanoverian rattail spoon by Sampson Bennet of Falmouth, c.1730

- LOT 75: A Charles I silver slip-top spoon, London, 1640, William Cary. Proce realised: £1560

- LOT 119: A George I silver spoon by Paul de Lamerie, London, c.1720. Price realised: £715

- LOT 88: A set of six George III silver 'Hen and Chick' picture-back teaspoons, London, c.1765. Price realised: £416

- LOT 73: Eleven Scottish provincial silver tablespoons by John Baillie (1740-1753), Inverness. Price realised: £975