Friday 28 April 2023

Aegidius Sadeler (1570-1629), engraving, after a painting by Esaye le Gillon), Zeynal Khan...

View MoreLot 327

Description

Aegidius Sadeler (1570-1629), engraving, after a painting by Esaye le Gillon), Zeynal Khan Shamlu, Prague, 1604, 19 x 14.9cm.

Provenance: Library of Tsarskoe Selo (Imperial Library at Tsarskoe-Selo as indicated by stamp on verso; this stamp being the stamp of the personal library of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia according to the catalogues of the books from Tsarskoe Selo at Princeton University).

Lot Footnotes

Inscription (Persian and Latin): (Janab-e raf at-e dastgah Zeynal Khan Shamlu keh az janeb-e navvab Persian and Latin): -e homayun-e ashraf-e ala be janab-e hezrat-eqeral saheb-e eqbal-eazam (H.E. the noble mighty Zeynal Khan Shamlu, who, on behalfof His Exalted Most Noble Royal Majesty, has come to His Royal Majesty, Lord of the Greatest Felicity). Synal Chaen Serenissmus Princeps in Persia Magni Sophi Regis Persarum ad Avgvstvm Caesarem Rvdolphvm II Laegatvs (Zeynal Khan, most serene prince, legate of the grand Sophi, king of Persia, to the His Imperial Majesty Rudolph II). Cum priui. S. Cae. M.tis Anno M. D.C.IIII. (with privilege of His Imperial Majesty, 1604). S: Cæs. M.tis sculptor Aegidius Sadeler ad viuum delineavit Pragae (made after life by His Imperial Majestys engraver Aegidius Sadeler in Prague).

Aegidius Sadeler was in 1570 at Antwerp to an artistic family and died in 1629 at Prague. His father was an art-dealer and his two uncles were engravers. His early career took him to Frankfurt, Munich and Rome where he worked with several artists who subsequently worked for the court of Rudolf II (Joris Hoefnagel, Hans von Aachen and Joseph Heintz the Elder). Once these artists moved to the Imperial court, they recommended Sadeler to the Emperor; in 1597 he was appointed to the court himself, where he became the most illustrious engraver of his time. Sadelers portrait of Zeynal Khan which shows him wearing a Persian robe and turban, is based on a miniature painting on vellum by the court-painter Essaye le Gillon on which Zeynal Khan had inscribed an inscription. But given that no one at the court in Prague could write Persian, Sadeler had to rely on the ambassador to produce for him a legible and abridged inscription for him to use for the engraving. Rudolf would have encouraged the production of the engraving from the painting he had commissioned, and the distribution of copperplates to publicise in order to emphasize the importance of his court as host to international visitors. He did this by the granting of a privilegium, a form of copyright that was granted to certain artists. Zeynal Khan would have similarly been interested in the wide distribution of the copperplate in order to publicize his embassy. The original painting was retained by the Emperor, but appears to have been sold when most of Rudolfs art collection was auctioned during the reign of Emperor Joseph II. It is now owned by The Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (Qatar).

Esaye le Gillon (aka Esaias le Gillon): Belgian painter who is known to have flourished between 1574 and 1606. He was the nephew of Carolus Clusius (aka Charles de lEcluse) the physician and botanist whom he followed to Vienna in 1574. It was for Clusius that he painted the 87 watercolours of mushrooms that now form the Codex Clusii held at the University of Leiden (Codex BPL 303). The university also owns a letter, as part of Codex Vulcanius 101, le Gillon wrote to Clusius in 1605 with which he enclosed a copy of his painting of the Persian ambassadors who had visited Prague in 1604 (Zaynal Khan Shamlu) and 1605 (Mehdi Qoli Beg) and Sadelers engravings of the two ambassadors. Le Gillon was already a painter at the court of Rudolf II in 1590 which is the earliest dated surviving letter which he sent to Clusius from Prague.

Zeynal Khan Shamlu: Safavid nobleman, who led an embassy of Shah Abbas II of Persia to the court of Rudolf II in Prague. The purpose of the embassy was to obtain Christian cooperation in confronting the Ottomans with a multi-front threat, with Zeynal Khans embassy being one of seven embassies dispatched to Europe to achieve this aim. Zeynal Khan departed Persia sometime in mid-1603 and arrived in Prague on 19 July 1604 to much fanfare. He and his party of 30 servants were given an escort of over one thousand men, mounted and on foot. Reports liken the arrival and procession across town to a parade. The ambassador met Rudolf II a week later on the 26 July, when he was received in the palace. The Persians presented Rudolf gifts of carpets and silk. It appears nothing of substance was discussed at this first meeting, for the reports describe exchange of pleasantries and magnificent entertainment, without mentioning discussion of political topics. However, after the meeting with the Emperor concluded, the ambassador had a more substantial meeting with Stefan Ferreri, the Papal Nuncio. The two discussed several topics in this meeting. They covered Papal relations with Persia, where Ferreri expressed a desire to see more Catholic orders established in Persia. They also discussed the lack of an Imperial representative in Persia, in contrast with the Vatican and Spain which had sent semi-permanent representatives. Ferreri informed Zeynal Khan that an Imperial ambassador, Stephano Kakasch von Zalokemeny, was under way. Finally, the Persian ambassador complained that the Spanish King had promised to go to war with the Turks, but he had not done so yet. Zeynal Khan had hoped to deliver his message to the Emperor, obtain a reply and quickly depart for home; however, things in the Imperial court did not move so quickly. Shah Abbas had requested a promise that the Christians would keep fighting the Turks, and that they would consult Abbas before making peace. This would be in line with the minimal expectation for a military alliance and would not allow the Turks to shift all their forces away from Hungary to face Persia. But Rudolf and the court were hesitant to make this promise. The war was putting a strain on Imperial resources. Already there were tentative offers of peace coming from the Ottomans, and some in the court were encouraging these offers to be accepted. Rudolf was indecisive and the court was divided. Already by the 9 August, Zeynal Khan was requesting that he be given leave to return home. But the Emperor kept postponing his departure. Instead, Rudolf arranged many activities for the ambassador, such as troop reviews and banquets. Eventually, word came from Moscow that another Persian diplomat was on his way to Prague. This gave the Emperor an additional excuse for postponing Zeynal Khans departure while he and the court pondered how to reply to Shah Abbas. Meanwhile, in 1605, the military situation was turning quite bad for the Imperial forces. Stephan Bocskay was now in charge in Transylvania and switched allegiance to the Ottomans. In addition to its own strategic value, this move also caused unrest in many Hungarian areas. The Turks took advantage to conduct an offensive which recaptured the fortresses of Visegrad and Esztergom, thus erasing the main Imperial strategic gains from the war. Ferreri speculated that Rudolf was waiting for a victory he could report to Shah Abbas before sending the ambassador home. Many voices in the court and the nobility were calling for a peace settlement with the Ottomans. But there were also equally strong proponents of continuing the war, notably the papal nuncio Ferreri, and perhaps the personal feelings of Rudolf himself. Finally, on 31 October 1605, the ambassador had his farewell audience. Ferreri also attended the audience and bid him farewell and gave him a letter for Shah Abbas professing his intentions to continue fighting the Turks and to send an embassy the following year. He also expressed these assurances personally. However, despite his assurances, on the same day Rudolf gave instructions to start peace negotiations with the Turks. Zeynal Khan who had been refused passage through Russia went first to the Netherlands and arrived home via a ship from Portugal shortly before May 1609. By the time he returned home, news had already made the messages he carried obsolete. Rudolf was forced to sign the Peace of Zivta-Torok in November 1606, breaking his promises to Shah Abbas. After his return, Zeynal Khan went on to high positions in the service of Shah Abbas and his successor Shah Safi. He was an ambassador to the Moghul court of Jahangir, he successfully led a defence of Baghdad against a Turkish attempt at recapture, and for that he was promoted to Commander-in-Chief of the army. But he suffered a disastrous defeat at the hands of the Ottomans at Mahidasht near Kermanshah on 4 May 1630 and was tried and executed on the orders of Shah Safi for this failing.

Fees & VAT

Buyer's Premium

The buyer shall pay the hammer price together with a premium thereon of 26% up to £20,000 (31.2% inclusive of VAT), 25% from £20,001 - £500,000 (30% inclusive of VAT), 20% from £500,001 thereafter (24% inclusive of VAT). The premium price is subject to VAT at the standard rate.

VAT

VAT is not charged on the hammer price unless it is stated that there is 'VAT applicable on the hammer price at the end of the description. Buyer's premium is subject to VAT.(ARR) - ARTIST'S RESALE RIGHT

Qualifying living artists and the descendants of artists deceased within the last 70 years are entitled to receive a re-sale royalty each time their work is bought through an auction house or art market professional.

It applies to lots with hammer value over £1,000 as follows:

0 to £50,000 - 4%

£50,000.01 to £200,000 - 3%

£200,000.01 to £350,000 - 1%

£350,000.01 to £500,000 - 0.5%

Exceeding £500,000 - 0.25%

ARR is capped at £12,500

Please note ARR is calculated in euros. Auctioneers will apply current exchange rates.

Export of goods

Buyers intending to export goods should ascertain whether an export licence is required before bidding. Export licences are issued by Arts Council England and application forms can be obtained from its Export Licensing Unit. Details can be found on the ACE website www.artscouncil.org.uk or by phoning ACE on 020 7973 5188. The need for import licences varies from country to country and you should acquaint yourself with all relevant local requirements and provisions before bidding. The refusal of any such licences shall not permit the cancelling of any sale nor allow any delay in making full payment for the lot.

Own a similar item?

Request a ValuationReceive alerts about similar lots

Get StartedContinue Browsing

LOT 328

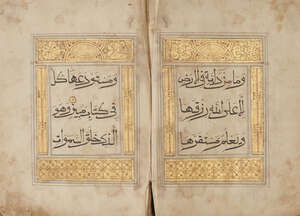

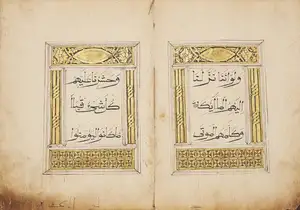

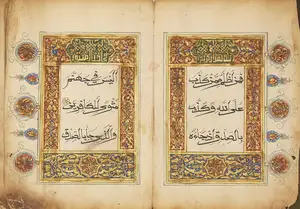

Juz 12 of a Chinese Qur'an, Surah Hūd (11), v.6 to surah Yūsuf (12), v.52, China, 18th...

Estimate: £300 - £500

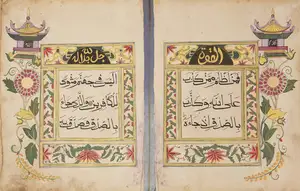

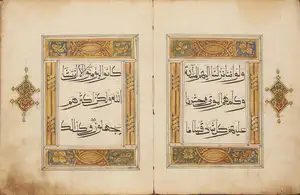

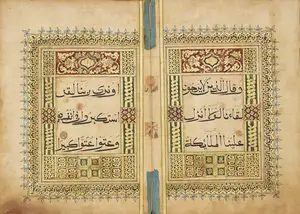

LOT 329

Juz 21 of a Chinese Qur'an, China, 19th century, Arabic manuscript on paper, 57ff. with 5ll. of...

Estimate: £600 - £800

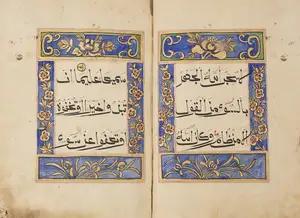

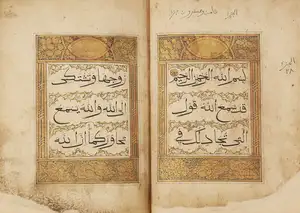

LOT 330

Juz 24 of a Chinese Qur'an, 60ff. Arabic manuscript on paper, with 5ll. of black Rayani script...

Estimate: £600 - £800

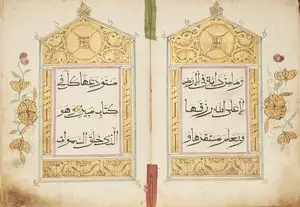

LOT 331

A Chinese Qur'an juz, with 5ll. of black Rayani script within double red rule, with gold rosette...

Estimate: £300 - £500

LOT 332

Juz 8 of a Chinese Qur'an, 59ff.,Arabic manuscript on paper, with 5ll. of black Rayani style...

Estimate: £200 - £300

LOT 333

Juz 8 of a Chinese Qur'an, 43ff., Arabic manuscript, with 5ll. of bold black Rayani script...

Estimate: £300 - £500

LOT 334

Juz 1 of a Chinese Qur'an, China, 19th century, Arabic manuscript on paper, 56ff., with 5ll. of...

Estimate: £500 - £700

LOT 335

Juz 12 of a Qur'an, China, 18th century, Arabic manuscript on paper, 56ff., with 5ll. of black...

Estimate: £500 - £800

LOT 336

Juz 24 of a Qur'an, China, 18th century, Arabic manuscript on paper, 57ff., with 5ll. of black...

Estimate: £800 - £1200

LOT 337

Juz 19 of a fine Qur'an, China, 18th century, Arabic manuscript on paper, 59ff., with 5ll. of...

Estimate: £800 - £1200

LOT 338

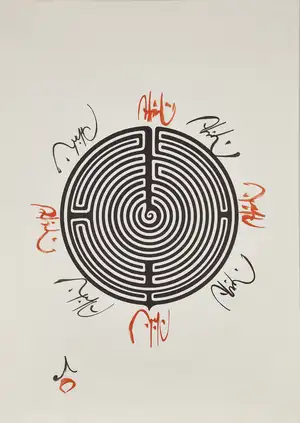

A Sino Islamic calligraphic work, 20th century, opaque pigments on paper, 50 x 70cm.

Estimate: £400 - £600

LOT 339

A panoramic view of Constantinople, Turkey, 1930s-40s, published J. Ludwigsohn, Constantinople,...

Estimate: £300 - £500

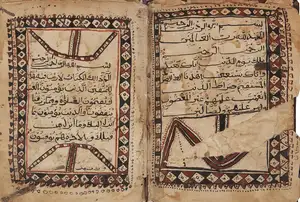

LOT 340

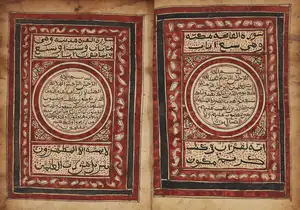

A rare example of an Ethiopian Qur’an, Harar, Ethiopia, 18th-century, Arabic manuscript on...

Estimate: £500 - £800

LOT 341

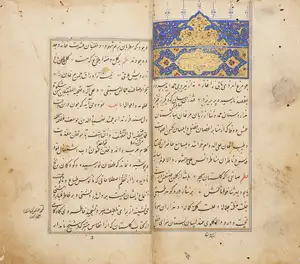

A Safavid copy of the Baharistan of Jami, dated 21 Sha’ban 954AH (16 October 1547AD), Persia,...

Estimate: £500 - £700

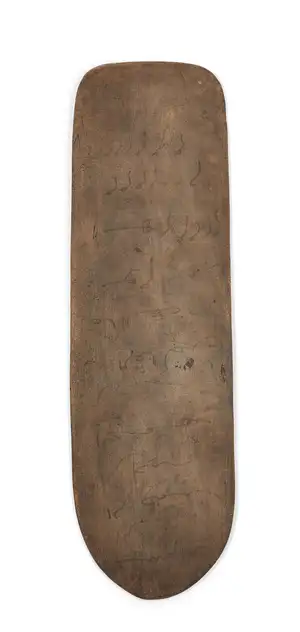

LOT 342

Two inscribed wood Qur'an boards (allo), Africa, 19th-20th century, of rectangular form, one...

Estimate: £500 - £700

LOT 343

A Qur’an section, Harar, Ethiopia, 19th century, Arabic manuscript on paper, 350ff. approx.,...

Estimate: £200 - £400

Newsletter Signup

Newsletter Signup

Keyword Alerts

Keyword Alerts

Would you like to receive personalised keyword alerts when new catalogues go live. If so, please indicate these below

Set a password to save your keyword alerts

Passwords are a minimum of 7 characters and must include an upper case letter, a lower case letter, a number and a special character (e.g., !@#$%^&*).